Noteworthy

- U.S. Interest Rate Cut Possibility Pushes Down Dollar and Bond Yields, U.S. Dollar on Track for Its Lowest Close in Months

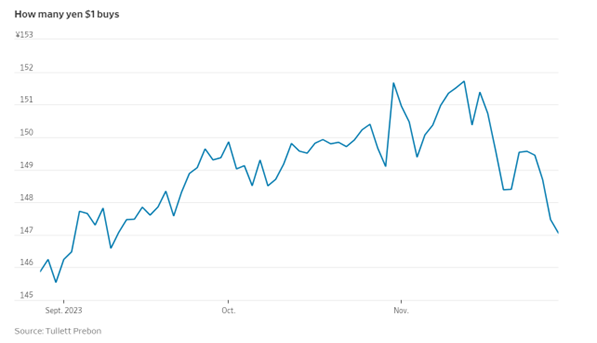

A Federal Reserve official’s view that U.S. interest rates should stay where they are for a while and perhaps be cut under certain circumstances sent the dollar to its lowest level in more than two months against the yen.

After changing hands at more than 150 yen earlier this month, the dollar fell as low as 146.65 yen during Wednesday morning trading in Tokyo, the lowest level since September 12, before recovering some ground. The U.S. dollar also fell against the euro currency.

Federal Reserve governor Christopher Waller on Tuesday hinted that the central bank could start lowering interest rates if the decline in inflation continues.

Waller said that “if we see this inflation continuing for several more months” then “you could then start lowering the policy rate just because inflation is lower.” Waller also said that recent progress in taming inflation should allow the Fed to extend its pause in rate increases at least into early next year.

The comments added to expectations that the interest-rate gap between the U.S. and Japan would stop widening, helping to push up the yen against the dollar.

SMBC Nikko Securities expects the dollar to weaken to below 140 yen in the first half of 2024, reflecting the possibility of a Federal Reserve interest rate cut. Even with its recent fall, the dollar is still strongly up against the yen compared to the beginning of this year.

Following falls in U.S. Treasury yields, the 10-year Japanese government bond yield fell to 0.675% Wednesday, the lowest level since September.

U.S. interest rate cut possibility pushes down dollar and bond yields.

Could the largest foreign buyer of American debt suddenly stop buying? Here is a comforting thought: This problem is probably already behind us.

At a time when government issuance is massively expanding and firms face a 2025 refinancing cliff, overseas investors have gone from holding 43% of U.S. debt a decade ago to holding just 30%. Adding to the worries, the

Bank of Japan might start raising interest rates next year, giving some Japanese owners a reason to repatriate their money.

The BOJ was alone among top central banks in leaving rates near zero even as inflation surged in recent years. The yen plummeted as money fled Japan, recently reaching its lowest level since 1971 in inflation-adjusted terms, data by the Bank for International Settlements shows.

BOJ Gov. Kazuo Ueda, who succeeded the ultra-dovish Haruhiko Kuroda in April, has started to buckle under the pressure. Ueda has been gradually dialing down his predecessor’s “yield curve control” policy. The yen has rebounded a bit over the past two weeks, suggesting that markets expect yields in Japan to keep rising.

For all the focus on China, Japan is actually the top holder of U.S. sovereign debt, with a total of $1.1 trillion. The BOJ’s ultra-loose monetary policy, now almost three decades old, created what analysts sometimes call the world’s biggest carry trade: Traders borrow yen at no cost, swap it for the currencies of countries that pay higher rates, and buy assets there to earn a pickup. U.S. Treasurys, corporate bonds, and loans are obvious targets, given their high yields and relative safety.

But rest easy: Japan isn’t about to stop financing the U.S. government. Many of the institutions that participate in this carry trade, including banks and some pension funds and insurers, avoid owning foreign currencies and use derivatives to hedge out the exchange-rate risk. They don’t care about the headline gap between U.S. and Japanese rates, but instead the gap after hedging costs.

As the unhedged pickup of Treasurys over Japanese bonds has hit new highs, the hedged pickup has become deeply negative and plumbed new lows. This is because of how this hedging is done, usually by rolling over three-month foreign-exchange swaps, which is an implicit bet on the shape of the U.S. yield curve. Since U.S. rates have risen more than Treasury yields—the yield curve has inverted—hedging costs have skyrocketed. Appearances aside, this popular carry trade has been a money-losing strategy since July 2022.

To be sure, some deep-pocketed Japanese institutions could move funds back home, because they don’t hedge their holdings. These include the officials who manage the country’s foreign reserves, as well as the mammoth Government Pension Investment Fund, which holds roughly $360 billion in foreign bonds and, according to a 2019 report, only hedges about 5% of them. Still, these steady investors haven’t really loaded up on U.S. bonds in the past two years, when the gains from doing so were massive. So, it is hard to see why they would now shift rapidly in the other direction.

Source: Refinitiv, prepared by Todd A. Blonshine

This is not a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any company, industry or security. The information and materials herein have been obtained from sources we consider to be reliable, but Comerica Capital Markets does not warrant, or guarantee, its completeness or accuracy. Materials prepared by Comerica Capital Markets personnel are based on public information. Facts and views presented in this material have not been reviewed by, and may not reflect information known to, professionals in other business areas of Comerica Capital Markets, including investment banking personnel.

The views expressed are those of the author at the time of writing and are subject to change without notice. We do not assume any liability for losses that may result from the reliance by any person upon any such information or opinions. This material has been distributed for general educational/informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation for any particular security, strategy or investment product, or as personalized investment advice.